Diabetes before insulin

We first got insulin in 1921. Before that type 1 diabetes was pretty much a death sentence within six months. It’s an old disease. The earliest descriptions exist on Egyptian papyrus from 1500 BC. In 600 BC Hindu physician Sushruta wrote about a disease of honey urine, which was diagnosed by tasting the urine or having ants gather around it. Glucose starts to spill into the urine at a blood sugar of 160-180 mg/dl (9-10 mmol/l).

That the sweetness was due to sugar was established in the 1700s by physician Matthew Dobson at the Liverpool infirmary. He had a patient who was passing fifteen liters of urine per day, and when his colorless urine evaporated a cake from sugar was left behind. Diabetic urine could also be fermented with yeast, where on the third day you were left with a liquid that had no sweetness and tasted like beer.

Low carbohydrate diets for diabetics go back a long time. Already in the late 1700s army surgeon John Rollo believed the sugar came from vegetables and recommended a meat-only diet. Rollo’s diet was an attempt to treat diabetes by preventing the formation of sugar. He based his theory on the observation that certain populations, such as the Eskimos, lived and thrived on a meat-only diet. This was successful in getting rid of the thirst and urination and became the preferred treatment by physicians at the time.

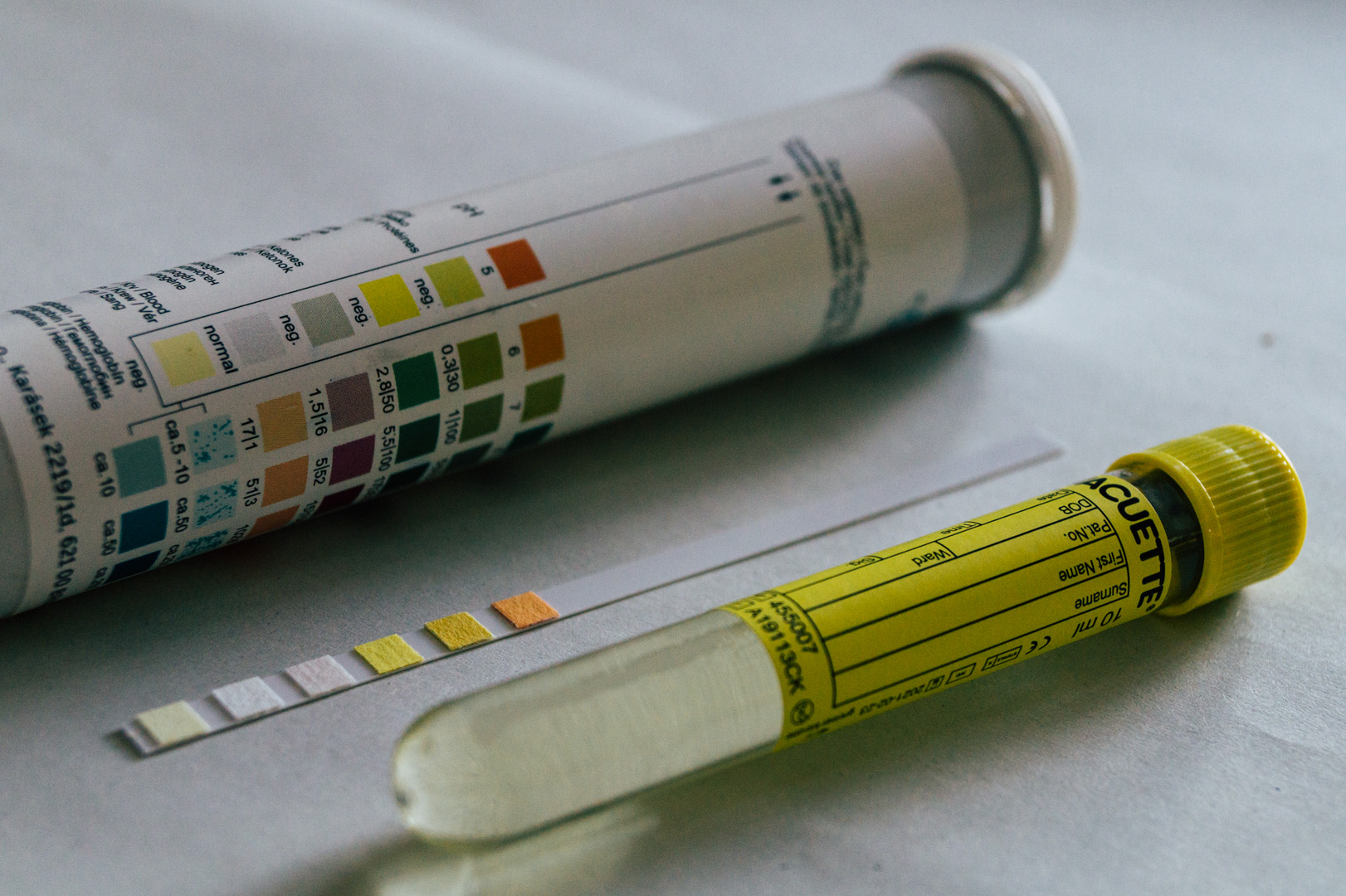

The 19th century saw chemical methods of measuring sugar in the urine. In 1841 Karl August Trommer invented the first urine glucose test with copper sulfate. Even though it was ideal for detecting glucose, many doctors found it too complicated and stuck to fermentation as a diagnostic tool. The ability to measure glucose with some accuracy made it possible to compare the impact of different diets.

During the 1850s there was a short fad of sugar feeding. It was created by French physician Pierre Piorry who reasoned that diabetics lost weight and felt so weak because of the amount of sugar that was lost in the urine. He thought that by replacing the lost sugar he would restore their strength. Patients were fed half a pound of treacle a day for four months, without any improvements.

Frederick William Pavy, who was a follower of Rollo’s low carbohydrate diet, came up with a variant of his own: the almond food diet. He considered a life without bread as the greatest privation and went on to invent almond flour as a substitute.

At the turn of the 20th century, physicians started promoting cures for diabetes based on specific dietary items. This included Mosse’s potato diet in 1902 and Von Noorden’s oatmeal diet in 1903. Many of these were semi-starvation diets.

During the Franco-Prussian war physician, Apollinaire Bouchart observed that glucose disappeared from urine in some of his patients as a result of starvation. The advice he gave to his patients was simple: eat as little as possible. For dieters, the outcome largely depended on whether you were fat or thin to begin with. While the fatter patients did well the thin, although adhering to the meat only diets, got sicker and fell into a coma. We know today that these would have been the type 1 diabetics, who develop ketoacidosis and die without insulin.

Another problem with diets was getting patients to stick to them. The search was on for drugs to treat diabetes. A US government publication from 1894 listed forty-two anti-diabetes drugs. Amongst them were bromide, uranium nitrate, and arsenic. We can feel lucky that science has advanced since then.

I learned this, and many other interesting things, while reading “Diabetes – the biography” by Robert Tattersall.