Correlation or causation?

When John Yudkin studied the potentially damaging effects of sugar in the 1960s, he correlated things like obesity and a high intake of sugar. What he didn’t have was causation. Proving causation is tricky when it comes to the human body because so many variables play a part. For this reason, we have total polarization in the field of nutrition today where no one agrees on what is good for you. Most people would go along with Michael Pollan’s famous conclusion: Eat food. Not too much. Mostly plants.

Still, it’s almost impossible to prove that eating a lot of plants is the cause of a long and healthy life. Causation applies explicitly to cases where action A leads to outcome B. Court cases against the tobacco industry have been complicated and dragged on for years. While there’s a clear correlation between smoking cigarettes and lung cancer, proving that cigarettes cause lung cancer is more difficult.

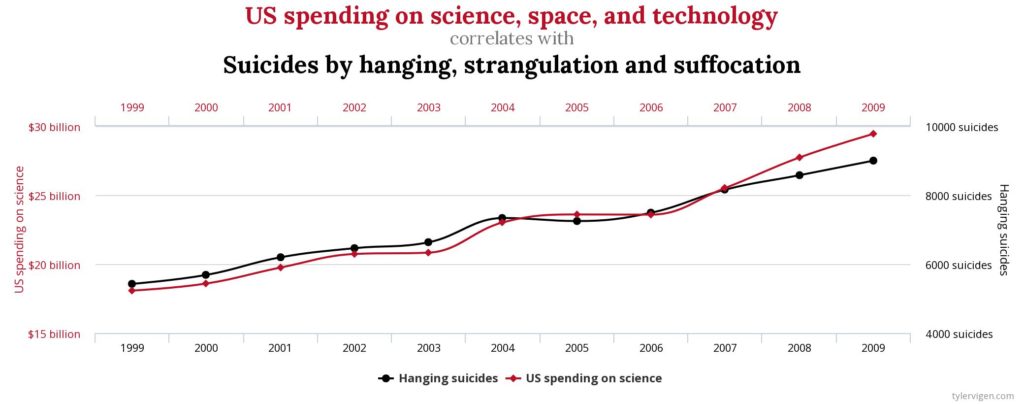

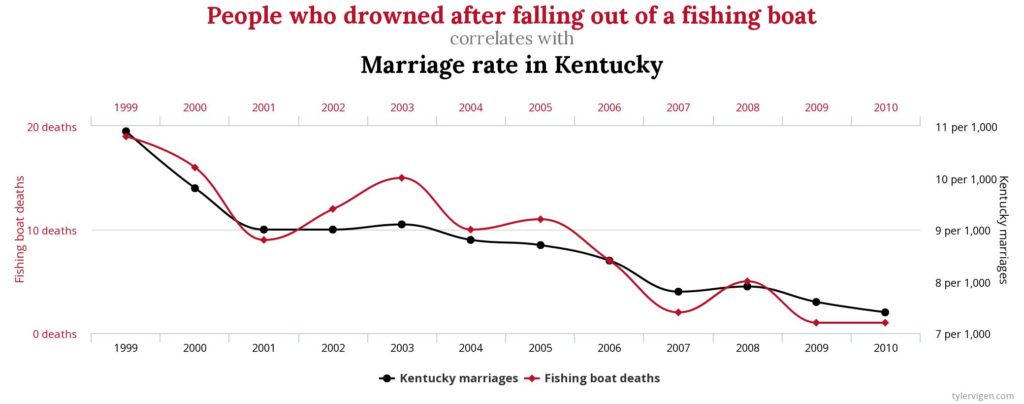

We often confuse correlation and causation as the human brain likes to find patterns even when they don’t exist. For this reason, we have to be careful with correlation studies that link things together. This point was brilliantly illustrated a few years back when Tyler Vigen set up the Spurious Correlations project as a fun way to look at correlations and to think about data.

Here he linked obscure things, like the number of people who drowned by falling in a pool with films that Nicholas Cage appeared in, or the per capita cheese consumption with people who died after becoming entangled in their bedsheets. I added some other examples below.

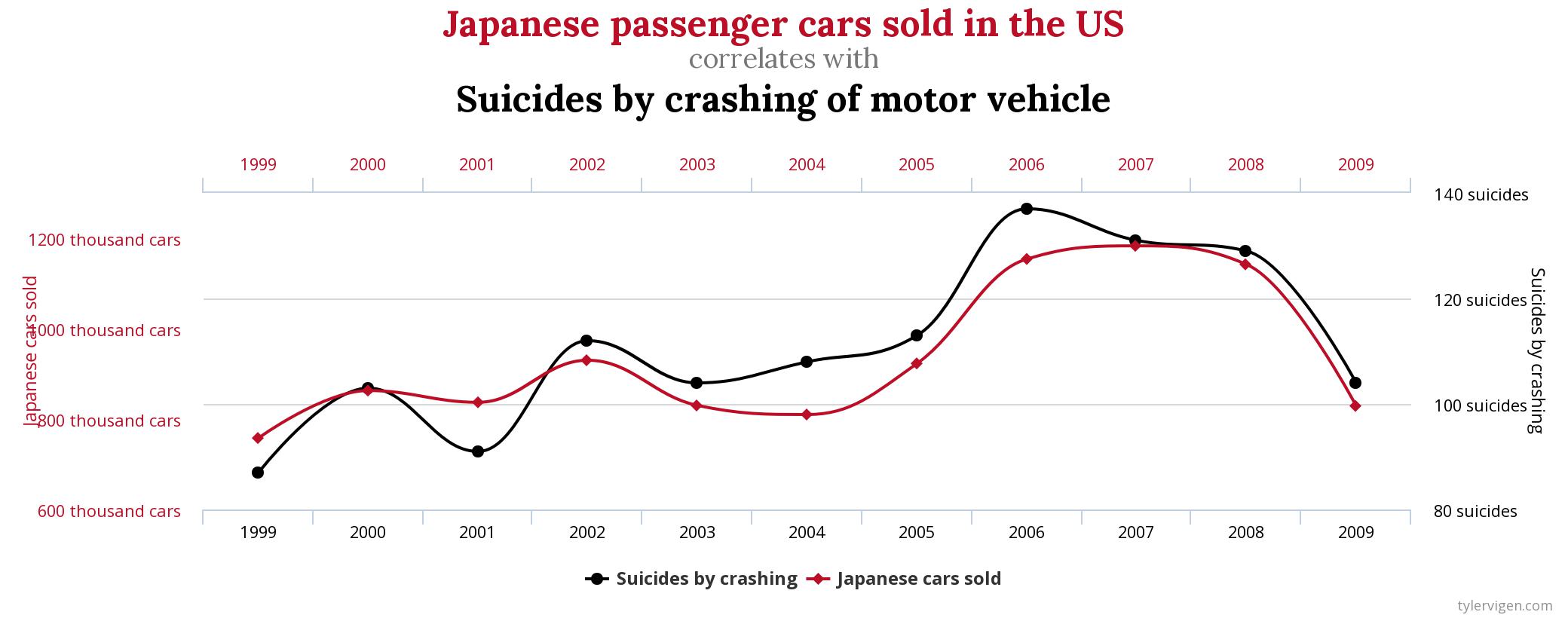

These examples show that even though correlation indicates that two events are linked, they can have no connection whatsoever. Correlation and causation are not the same things. When you analyze any data, keep in mind that the number of Japanese motor vehicles sold in the US correlates with the suicides by crashing of motor vehicles. Interesting, right?

All images in this post are taken from Spurious Correlations.